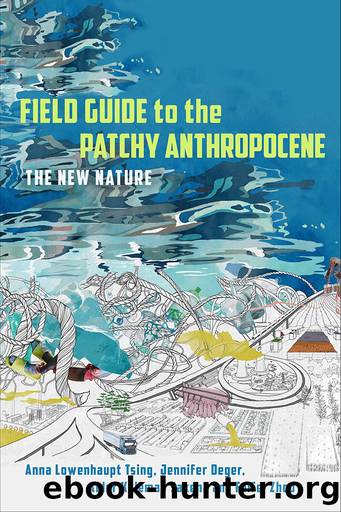

Field Guide to the Patchy Anthropocene by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing

Author:Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Stanford University Press

Published: 2024-05-15T00:00:00+00:00

Between the early eighteenth and the mid-nineteenth centuries, the British navy experienced a serious setback: Its ships began to rot before they could even set out to sea. In his report on this history, John Ramsbottom writes: âThe duration of a ship was estimated at twenty-five to thirty years in the seventeenth century, about twelve years from 1760 to 1788, about eight years during the Napoleonic period, dwindling to âno durationâ immediately after Trafalgar.â8 The problem was the dry rot fungus. It was the âdeath-knell of wooden war ships,â solved only by the introduction of ironclad ships such as the British Thunderer in 1863.9

The following is clear: Humans did not invent destructive fungi. Destructive fungi have existed a lot longer than humans. But Anthropocene infrastructures have succeeded in the round-the-world spreading of some fungi that otherwise would have remained in circumscribed places. It is that spread, in many cases, that has caused all the trouble. It is that spread that counts, in this section, as a âferal biology.â

Dry rot (Figure 35), caused by the fungus Serpula lacrymans, is not a pathogen; it eats dead wood. The fungus is only important if it happens to infect a valued piece of dead wood, such as a ship or a house. It makes a good protagonist for this part of the story only because it shows how fungi have been transported around the worldâin this case, as part of imperial ships. In its natural habitat, S. lacrymans is a specialist that competes poorly with other fungi; it lives on dead wood in shade at the cool, dry tree line.10 In the protected environments of human construction, however, it thrivesâand proliferates.

The distribution of Serpula lacrymans has confused geneticists. Because one variant is so widely distributedâin human habitationsâacross Europe and North America, the search was on for its wild relatives. Several scattered relatives were found, but the closer researchers looked, the more different these relatives appeared from the kind that lives in ships and houses, which they dubbed the âcosmopolitanâ variant.11 There are indeed wild dry rots in mainland Asia, but they are rare, parochial, and specialized. Furthermore, the cosmopolitan variant has a very small genetic range, suggesting recent introduction. Geneticists are wary of more-than-human histories, which cannot be tested with their methods. However, most authorities have come to accept the idea offered by South Asian âfungus huntersâ in the early twentieth century: Dry rot was transported around the world by the British use of logs from the western Himalayas.12 They quote Ramsbottom:

Foreign timber was often floated down rivers and then immediately loaded into the confined holds of timber ships, an ideal arrangement for fungal infection; the logs were sometimes covered with fruit-bodies before they reached the dockyards.13

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(31444)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31035)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(30982)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(22896)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(18124)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(13157)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(12999)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(12834)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(12491)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(11983)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(11960)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(8410)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(7897)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(6531)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(6447)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(5816)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(5577)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(5094)

We Need to Talk by Celeste Headlee(4920)